|

|

TEMPORARY

EXHIBITS:

GRAND

MANAN AND THE WAR OF

1812

M. J. Edwards, Editor -

Curator/Director,Grand

Manan Museum

|

|

This small

booklet was produced as

a supplementary

companion to the five

commemorative plaques

which the museum

received funding for in

the spring of 2013

through a grant from the

Government of Canada

through the Department

of Canadian Heritage

1812 Commemorative Fund.

The plaques were erected

in the summer of 2013.

|

|

|

|

|

It is hoped that

the information contained herein

provides some context for the

many events on land and sea

which took place in the Bay of

Fundy near and on Grand Manan

during the span of this war

(1812-1814). The plaques contain

a condensed version of the

information found here.

Laurie Murison,

Chair of the Swallowtail Keepers

Society and Director of the

Whale & Seabird Research

Station, was invaluable as a

primary motivator in the

application for the grant. She

also assisted with the grant

writing and helped to design the

plaques, one of which is

situated at Swallowtail.

Thanks to board

member Greg McHone for producing

the original booklet through his

home publishing business at

cost. Island artist Janie

Hepditch-Vannier graciously

agreed to do some interpretive

ink and watercolour paintings

for us, illustrating three

stories relating to events which

took place on and near Grand

Manan during the War of 1812.

They help to bring the stories

alive for us.

|

Thanks to Ava

Sturgeon of the Grand Manan

Archives for her assistance with

the photographs, maps and

diagrams for the proposed Net

Point Fortifications and the

Machias Seal Island lighthouses.

|

We

acknowledge

the financial

support of the

Government of

Canada through

the Department

of Canadian

Heritage 1812

Commemoration

Fund.

|

Nous

reconnaissons

l’appui

financier du

gouvernement du

Canada par

l’entremise du

ministère du

Patrimoine

canadien Fonds

de commémoration

de la

guerre de 1812.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Introduction

From June 18, 1812

to February 16, 1815, Canada was

the battleground in a war

between the United States and

Great Britain. If the American

invasion of 1812-1814 been

successful, Canada would not

exist. The war ended with the

signing and ratification by the

United States Congress of the

Treaty of Ghent, beginning a

long period of peaceful

relations which remains to the

present day.

Causes of

the War

The United States

declared war on Great Britain

because of a number of factors:

the Royal Navy’s practice of

impressment of American merchant

sailors into the Royal Navy;

trade restrictions resulting

from Britain’s war with France;

British support of Indian tribes

attempting to block westward

expansion; and an interest in

annexing Canada. They were met

with more resistance than

expected and their invasion was

defeated, however the practice

of impressment did finally end

with this war (Adapted from

Wikipedia: War of 1812).

The War of

1812 and Grand Manan

“During the period

of 1812-1814, the Bay of Fundy

was infested with privateers.

Settlers of the island saw much

hardship during these years, as

privateers from both sides

occasionally raided villages

along Grand Manan's east shore

and plundered their belongings.

Much of eastern coastal Maine

near Grand Manan was occupied by

British military forces during

and after the war, with Eastport

not freed until 1818”

(Wikipedia: Grand Manan).

|

Each of the five

plaques that are situated around

the island tell a small part of

the tale of what occurred in

these waters, in this part of

the Fundy and Passamaquoddy

Bays, during the War of 1812. At

this time in history, the

boundary between Maine and New

Brunswick was fluid in every

sense of the word. Families

often lived split between the

two countries, and many island

settlers arrived here from

Massachusetts and Maine. Trade

between the two countries was

abundant and war was seen as an

inconvenience and an economic

disaster for many.

The privateers who

participated in this war,

however, were those who profited

most. Many personal fortunes

were made, some banks and

universities founded, with the

profits from legal plunder of

enemy ships. A “letter of

marque” was the official

document of a privateer vessel

that granted permission from

their government to chase down,

capture and seizure an enemy’s

ships and their goods, and it

mattered not if they were naval

ships or merchant ships.

Dalhousie University in Halifax

and the Canadian Imperial Bank

of Commerce (CIBC) were both

founded with privateer money.

Occasionally

American privateers would harass

Grand Mananers and steal their

boats, hide from British

cruisers behind the smaller

islands of the archipelago, or

take shelter in its many natural

harbours. The British Navy would

also send recruitment boats to

shore looking for and seizing

able-bodied men to impress into

their navy. Life in the British

Navy was not something to be

desired, and many a sailor

jumped ship and took refuge on

American naval ships. If a

sailor was American, but had

been born British, the British

claimed him and did not

recognize his American

citizenship. This was a main

grievance behind the outbreak of

the war.

|

| |

|

|

|

There

is a commemorative plaque at

Swallowtail Peninsula facing Net

Point. Net Point is situated

between Pettes Cove and Flagg’s

Cove.

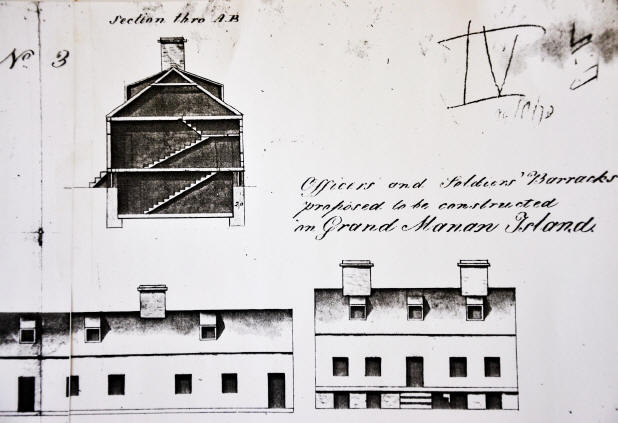

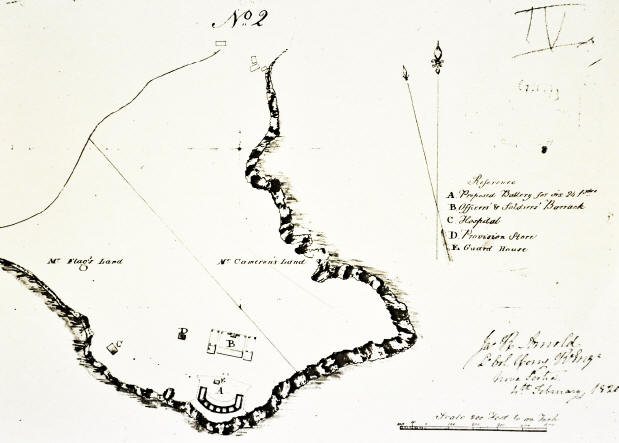

PROPOSED

FORTIFICATION FOR NET POINT

AND SWALLOW TAIL – 1819

Fortification of

Grand Manan was considered as

early as June 30, 1808, when

Capt. Nicholls of the Royal

Engineers wrote to Lt. Gen. Sir

George Prevost as follows: “I

cannot omit remarking that the

Island of Grand Manan is

settling fast, population

reconed [sic] between 4 and

500, Militia at 60, is healthy

and possesses a good harbour

for small vessels, and, as

from its situation it may be

considered as the key to the

Bay of Fundy I should think it

worthy of very serious

consideration” (Buchanan

27).

In 1875 another

writer demanded “that the

island be fortified and

developed, claiming that its

situation, either for commerce

or war, is strategically as

valuable as those of the Isle

of Man, Guernsey, and Jersey,

and that it would make a fine

point of attack against

Portland and the coast of

Maine” (Buchanan 27).

The following four

paragraphs are quoted in their

entirety from The Grand

Manan Historian, No. V, Charles

Buchanan (Ed.), pp.

26-27, 1938:

|

“During the war

between Great Britain and the

United States, from 1812 to

1814, the Bay of Fundy was

infested with American

privateers, and the commerce of

the provinces suffered in

consequence. The waters

surrounding Grand Manan were a

famous lurking place for these

rapacious corsairs until British

cruisers became numerous on the

seas, when their occupation

ceased. The return of peace was

hailed by the people of both

countries, but the boundary

controversy began, and for years

threatened to involve the two

countries again in war.

In 1817 Grand

Manan, and other islands in

Passamaquoddy Bay claimed by the

British, were declared a part of

Great Britain. In 1819 it was

decided to fortify Grand Manan,

for which purpose 40,000 lbs.

was voted by the imperial

parliament, and on September

14th, 1819, Colonel Lord, with

two officers of the Royal

Engineers, proceeded to the

island to select a suitable

position. In reference to this

matter the St. John [N.B.]

Courier of November 6th, 1819,

contained the following:

‘The intended

fortifications on Grand Manan

are, we understand, to be

immediately commenced at that

point of the island called

‘Swallow Tail,’ being the spot

most approved for that

purpose, and establishing a

depot, in the vicinity of

which there is a spacious bay

and safe anchorage for ships,

secure from all winds except

the eastward.1

|

|

The

commanding situation of

Grand Manan, and the

many places of natural

strength it possesses,

made the retention of

the island by the

British of great

importance, hence the

determination to fortify

and defend it if

necessary. But

fortifications were

fortunately not required

on Grand Manan, the

rightful claims of Great

Britain to the island

were peacefully

conceded, and the key to

the entrance of the Bay

of Fundy remained under

the British Flag”

(Buchanan, 26-27)

|

|

The photos showing the plans

for the Net Point Fort are

taken from a collection of

drawings by the Royal Naval

Engineers housed in the Grand

Manan Archives.

|

| |

|

WHISTLE

LONG-EDDY PLAQUE

|

|

There

is a commemorative plaque at

the end of the Whistle Road,

beside the bench which

overlooks Passamaquoddy Bay

and faces the coast of Maine.

PRIVATEERING:

THE WEAZEL INCIDENT AND GRAND

MANAN

In

New England, Maine suffered the

most from the war. Early in the

war there was Canadian

privateering action and

harassment by the Royal Navy

along the coast. On September

1813, there was combat off

Pemaquid between HMS Boxer

and USS Enterprise,

killing both commanders and

gaining international attention.

Largely unprotected by the U.S.

Army and small U.S. Navy, in

1814 the district was invaded

and large parts of coastal Maine

were occupied by the British.

Legitimate commerce all along

the Maine coast was largely

stopped, creating a critical

situation for a shipping

dependent area. An illicit

smuggling trade with the British

soon developed, especially at

Castine and Eastport. Maine’s

extreme vulnerability during

this war gave impetus to its

movement toward statehood which

occurred in 1820 (Adapted from

Wikipedia: History of Maine).

Grand Mananers

historically have had strong

ties with Maine, and many island

settlers originally came from

Massachusetts or Maine. After

the war the islanders kept close

and good relations with their

Maine coastal neighbours because

of strong commercial trade and

family ties.

21

September 1814:

The British

establish a Customs Office at

Castine, District of Maine,

which becomes a designated

commercial headquarters of the

occupied territory.

Announcement that

trade with the enemy was legal

through Castine made the

mercantile communities of Saint

John, New Brunswick and Halifax,

Nova Scotia very happy. Customs

officials amassed £10,000 in the

eight months that they were

there. After the war, the

“Castine Fund” was directed by

the British government to be

used for public improvements in

Nova Scotia, where it built a

new library for the British

garrison and Dalhousie College

(now Dalhousie University). (Adapted

from Canada’s Historic

Places, “War of 1812 Timeline:

July 1814-December 1814”.)

|

Privateering

The Bay of Fundy

was a secondary theatre of the

war where “hunting warfare”,

whereby each side attempted to

capture enemy merchant ships and

protect their own from seizure,

was the common practice. These

activities were carried out by

small naval vessels and privateers,

privately owned vessels granted

government licenses (known as

“letters of marque”) to seize

enemy ships and their cargo

during war time. This hindered

the enemy’s economy but often

allowed friendly cargo vessels

and fishing vessels to proceed.

The summer of 1812

saw the capture by the British

of 24 American privateer vessels

comprised of 18 schooners, 2

sloops, 2 brigs, 1 revenue

cutter and 1 ship of the line in

or near the Bay of Fundy.

Privateering was a profitable

business for those who owned the

boats, and crew members shared

in the profits. The goal was to

interfere with British shipping

leaving the ports of St. Andrews

and Saint John. Others saw the

privateers as a costly nuisance

that interfered with essential

shipping trade and the

distribution of food and goods.

(Adapted from Smith 32-39).

The

Weazel Incident and Grand

Manan

“Many privateers

were apparently no better than

pirates, and one such man was

Edward Snow, commander of the Weazel

and a preacher of the gospel

from Hampden, Maine. On June

9th, 1813 he sailed to Beaver

Harbour, NB, robbed Captain

Young’s house of 15 barrels of

sugar, his family’s clothing and

even the children’s toys. Later

the same night he captured a

vessel bound for St. Andrews

from Saint John, but when news

of his exploits reached

Campobello the next day, two

boats were sent in pursuit. The

stolen vessel was soon

recaptured and the Weazel

chased to Grand Manan, where

Snow and his crew were driven

into the woods on the south

western shore, and one crew

member was captured. The men

found their way to Seal Cove

where they stole a large boat

from Alexander McLane, and

presumably made their escape to

Cutler, Maine” (Buchanan 60-61).

“Before

the incident with Snow and the

Weazel, British cruisers

in the Bay of Fundy had never

interrupted American fishing

boats in their pursuits, but

Captain Gordon of the ‘Rattler’

now ordered them off, and gave

notice that such as were found

beyond certain prescribed limits

would be captured and destroyed”

(Buchanan 61).

|

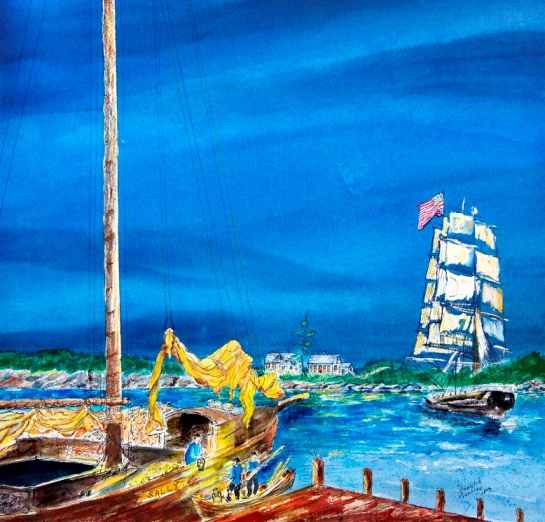

“The Weazel Incident”

watercolour on paper, 18”x18”,

by Janie Hepditch-Vannier,

2013.

“The Weazel Incident”

watercolour on paper, 18”x18”,

by Janie Hepditch-Vannier,

2013. |

| |

|

BONNY

BROOK PLAQUE

|

|

There

is a commemorative

plaque near the White

Head Ferry landing at

the end of the Ingalls

Head Road.

PRIVATEERING,

GRAND MANAN, AND THE

BONNY’S BROOK INCIDENT

“During

the period of

1812-1814, the Bay of

Fundy was infested

with privateers.

Settlers of the island

saw much hardship

during these years, as

privateers from both

sides occasionally

raided villages along

Grand Manan's east

shore and plundered

their belongings” (Wikipedia:

Grand Manan Island).

History

of Bonny Brook,

Ingalls Head: Named

for Joel Bonney, one of

Grand Manan’s earliest

settlers: In 1779

Loyalists Joel

Bonney, Abiel and James

Sprague and their

families moved from

Machias, Maine to Grand

Manan seeking peace and

shelter. In

1780,

Joel’s son, Alexander

Bonny, was reported to

be the first white baby

born on Grand Manan.

However, the families

found living on Grand

Manan too difficult and

so returned the same

year to Digdeguash, NB

where they had lived

before.

|

“The Sally Incident

at Bonny Brook”,

watercolour on paper,

18”x18”, by Janie

Hepditch-Vannier,

2013.

“The Sally Incident

at Bonny Brook”,

watercolour on paper,

18”x18”, by Janie

Hepditch-Vannier,

2013. |

|

|

The Sally

Incident at Bonny’s Brook: “In

the American War of 1812, Grand

Manan, from its isolated

position, became a favourite

rendezvous for privateers and

piratical crafts, and British

cruisers had many an exciting

chase to catch them. On one

occasion an American privateer

entered Grand Harbour and seized

a vessel in Bonny’s Brook while

quietly riding at anchor…the

privateersmen, having caught one

vessel, felt eager for another,

and…pounced upon [the] schooner

Sally, owned by Wooster and

Ingalls, who, anticipating a

visit from Yankee privateers,

had removed a plank from [the]

bottom, which of course rendered

the craft altogether

unseaworthy. The privateers

attempted to repair damages, but

failed in the attempt, and

Wooster and Ingalls were left in

possession….” (Buchanan 60).

Profits

are Made from Privateering: Many

private fortunes were made from

privateering during the war.

Some enterprising businessmen

had ships built for privateering

and hired crews to run them. The

Liverpool Packet, a

schooner from Nova Scotia was

one of the most famous of the

privateer vessels, capturing 50

American prizes during the war

and making wealthy its owner,

William Collins, and its

Captain, Joseph Barss. One of

the wealthiest men of his day,

Collins founded the Halifax

Banking Company, which later

became the Canadian Imperial

Bank of Commerce (CIBC) (Adapted

from Butts).

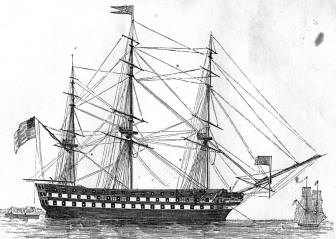

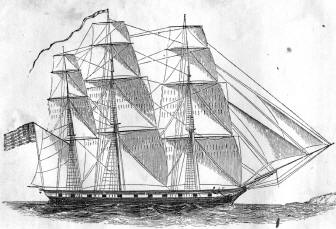

Sailing

Ships Used during the War of

1812:

- Brig:

two square-rigged masts,

carried 10-20 guns, quick

but required a large crew,

served as couriers and

training vessels.

- Frigate:

square-rigged on all three

masts, fast, 28 guns, used

for patrolling and escort.

Most famous was the HMS

Shannon which captured the

USS Chesapeake and towed it

back to Halifax.

|

- Schooner:

elegant, manageable, two

masts, main and shorter

foremast, gaff-rigged,

popular as transports and as

privateers.

- Ship of the

Line: 60-100

guns, large fighting ships,

the ships formed two

opposing lines and battered

away at one another.

- Sloop:

smaller than a frigate, 20

guns, single-masted,

fore-and-aft-rigged,

formidable fighting ships.

Built and used by the

British to capture the

menacing American

privateers.

Notable

American Privateers

included the Fame, Growler,

Revenge, and Wasp,

of Salem, Massachusetts and the

Lily of Portland, and the

Industry of Lynn,

Maine.

Notable

British Privateers included

the frigates Spartan

and Maidstone, sloops

of war Fantome, Rattler,

Indian, Emulous, and Martin,

brigs Plumper and Boxer.

The schooner Breame was

dreaded for her activity and

success, although smaller than

either the brigs or the sloops,

and the Spartan and Maidstone

were very successful in

capturing American privateers

cruising the Bay of Fundy in

1812 (Adapted from Kilby).

The following

steel engraving illustrations of

American naval sailing ships are

from The Kedge Anchor: or,

Young Sailor’s Assistant,

Wm. Brady, Sailing Master, U.S.

Navy, 2nd edition, R.L. Shaw,

222 Water Street, New York,

1857. (A second edition of this

book was owned by a Grand Manan

sailor, Judson Foster, captain

of the Snow Maiden

which operated as a mail sailing

ship until the late 1930s,

bringing island mail to the

Newton’s Wharf behind the

current day Home Hardware

store.)

|

Brig-of-War (American) |

Frigate (American) |

Schooner-of-War

(American) |

Ship-of-the-Line

(American) |

Sloop-of-War (American) |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

There

is a commemorative plaque in

Seal Cove located beside

McLaughlin’s Wharf Inn.

THE

POTATO INCIDENT AT SEAL COVE:

A TEST OF LOYALTY

The War of 1812

tested the loyalty of some

Americans living on Grand Manan

who had signed an oath of

allegiance to King George III, a

requirement for obtaining a land

grant.

|

Dr. John

Faxon, an early

medical doctor on Grand Manan,

arrived from the United States

in 1808 and settled at Seal

Cove. A noted walker, he would

visit the sick in their homes

and walk many miles for

enjoyment and exercise. Dr.

Faxon’s lasting legacy, the

result of his enterprising

spirit and engineering skill,

was the creation of Seal Cove

Harbour. He organized men to cut

a passage through the natural

sea wall, opening up the

picturesque cove to the open Bay

of Fundy waters. In 1811 Dr.

Faxon also launched the first

full-rigged and largest ship

ever built on Grand Manan, the

full-rigged 500 ton John,

c. 1811. When the War of 1812

broke out, however, Dr. Faxon

hastily returned to the United

States and his property reverted

to local residents (adapted from

Hill 24).

|

|

Joseph

Blanchard, unlike

Dr. Faxon, remained on

Grand Manan when war

broke out. Blanchard,

like Faxon, had received

several large land

grants in Seal Cove,

some of which he

actively farmed. One day

he was visited by a

privateer who haughtily

demanded a supply of

potatoes. Blanchard

refused to comply with

the demand, telling the

privateer that as he was

now a British subject he

would not ‘afford

succor or feed the enemies

of King George.’ ‘However,’

said he, pointing to the

potato field, ‘there

are the potatoes, and

if you are rascals

enough to steal them –

you must dig them.’

Such spirited response

demonstrated his loyalty

to the British and his

new home and may have

saved him from further

aggressions (Buchanan

60).

|

“The

Potato Incident at

Seal Cove”,

watercolour and ink

on paper, 18”x18”,

by Janie

Hepditch-Vannier,

2013.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

There

is a commemorative plaque at

Southwest Head along the cliff

to the left of the lighthouse

parking. This plaque faces

Machias Seal Island.

MACHIAS

SEAL ISLAND OWNERSHIP DISPUTE:

A WAR OF 1812 LEGACY

Introduction

Machias Seal

Island is located between the

Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine

near Grand Manan Island, NB and

Cutler, ME. Canada has

maintained a lighthouse there

since

|

1832 and has

always manned the light with two

keepers paid by the Canadian

Coastguard. The island is also a

noted puffin breeding colony and

terns, until recently (they have

all disappeared as their food

source dwindled or relocated due

to warming water temperatures),

were also a great tourist draw.

For a number of years now boats

from both countries have taken

turns landing a limited number

of visitors (limit is 13 people)

each day on the island during

the summer months when puffins

are breeding on the island.

There are also biologists on the

island during the breeding

season.

|

Machias Seal Island

with the three towers,

two of which are

lighthouses, c. 1920s.

Machias Seal Island

with the three towers,

two of which are

lighthouses, c. 1920s.

Photo from the Grand

Manan Archives. |

(The

following information

is adapted from Wikipedia:

Machias Seal Island)

Machias

Seal Island: A Few

Facts

Machias Seal Island is

a migratory bird

sanctuary of

approximately 20 acres,

treeless, with a

population of two, lying

16 km (9.9 mi) SE of

Cutler, Me, and 19km

(11.8 mi) SW of

Southwest Head, Grand

Manan, NB.

The first lighthouse

was constructed in 1832

by the British

government after Saint

John shipping merchants

exerted pressure upon

the government,

requesting a light to

protect shipping in an

area often shrouded in

fog with many dangerous

ledges and shoals.

The island was staffed

by Canadian Coast Guard

employees until the

early 1990s when all of

the lighthouses on the

Atlantic coast became

automated. Today, the

two staff living on the

island remain for

sovereignty purposes and

are paid by the

Department of Foreign

Affairs (through the

Coast Guard). Machias

Seal Light is the only

manned lighthouse

remaining in Canada.

|

|

|

The island was

staffed by Canadian Coast Guard

employees until the early 1990s

when all of the lighthouses on

the Atlantic coast became

automated. Today, the two staff

living on the island remain for

sovereignty purposes and are

paid by the Department of

Foreign Affairs (through the

Coast Guard). Machias Seal Light

is the only manned lighthouse

remaining in Canada.

In 1979

there was a “Joint

application to the

International Court of Justice

(ICJ) at The Hague”

in the Netherlands, but both

countries avoided having the ICJ

rule on the sovereignty of the

Machias when determining the

starting point for the offshore

boundary for fishing and mineral

exploration purposes on Georges

Bank, which was set at

44°11’12”N 67°16’46”W.

In 1984 the

ICJ ruling “Delimitation

of the Maritime Boundary in

the Gulf of Maine Area

(Canada/United States of

America)” highlighted

a gap of several dozen

kilometers between 1984 Gulf of

Maine boundary and the present

day International Boundary, and

this placed both Machias Seal

Island and North Rock in the

middle of a “grey

zone”, which

is what fishermen on both sides

now call the area.

This grey

zone has lead to an

ongoing exploitation and

overfishing of valuable lobster

and other species by both sides

in this area.

|

For decades now

this remote migratory bird

sanctuary has found itself in

the news, and there is ongoing

concern that this small island

may someday lead us back into

conflict if the sovereignty is

not soon resolved.

Some

Boundary History

The 1814 Treaty of

Ghent re-established borders

between the U.S. and present day

Canada to their 1811

configuration. It also called

for a joint British-U.S.

Boundary Commission to resolve

the disputed territory of

several islands in Passamaquoddy

Bay, including Grand Manan,

which were claimed by both

sides.

In 1817, this

Boundary Commission declared

that Moose, Dudley, and

Frederick Islands belonged to

the United States, while Grand

Manan and the other islands of

the Bay belonged to Canada.

Unfortunately,

this treaty, and subsequent

commissions, failed to mention

or deal with Machias Seal Island

because it is not an island of

the Passamaquoddy Bay. It is,

consequently, the only remaining

unresolved boundary dispute

between the United States and

Canada, with both countries

claiming sovereignty. This was

never much of an issue until the

1970s when the Americans decided

they wanted access to the rich

fishing grounds in the area

(Adapted from Wikipedia:

Machias Seal Island).

|

| |

|

In The News

Recently

National

Post headline, Nov

27, 2012: “Puffin Wars: The

Island paradise at centre of

last Canada-U.S. Land

dispute.”

The Canadian Press

headline, Dec 23, 2012: “

Tiny island subject of

dispute between Canada and

U.S.”

Maclean’s Magazine,

Jan 7, 2013: “Does Canada or

the U.S. own Machias Seal

Island?”

The

Last Canada-U.S. Boundary

Dispute

International Boundary

Dispute: Historical

Timeline (Bay of Fundy):

The following excerpts are

adapted from the International

Boundary Commission: The

History – The Historic

Treaties of the Boundary

Commission, web,

unless otherwise noted.

1783 The Definitive

Treaty of Peace: Defined

the boundary between the

newly-formed United States

and British North American

colonies from the “mouth of

the St. Croix River in the

Bay of Fundy…”

1794 Jay’s Treaty:

Provided two

Commissioners to decide what

river was the St. Croix.

1814 Treaty of

Ghent: Appointed

two Commissioners to decide

the sovereignty of several

of the islands in

Passamaquoddy Bay, including

the island of Grand Manan

with its rich fishery. The

Fourth Article of this

Treaty explains how the

United States claimed Grand

Menan and several other

islands in the Bay as being

within their boundaries

(being within 20 leagues of

their shores), and that

Great Britain claimed the

islands as being with the

limits of the Province of

Nova Scotia, as predating

the Treaty of 1783.

1817 Commissioners’

Report (November 25): “The

commissioners appointed

pursuant to the Treaty of

Ghent determine that Moose,

Dudley, and Frederick

Islands belong to the United

States, but that all other

islands in Passamaquoddy

Bay, and Grand Manan Island

in the Bay of Fundy, are

part of New Brunswick”

(Canada’s Historic Places.

War of 1812 Timeline:

January 1815-1871).

Following the

appointment of Thomas

Barclay and John Holmes as

the British and American

Commissioners respectively

who were appointed to

resolve the 1817 Eastern

Boundary of ownership of the

islands in Passamaquoddy

Bay, the Hon. Ward Chipman,

contacted Moses Gerrish, a

Harvard graduate and the

Loyalist leader of the

settlement of Grand Manan,

which took place on May 6,

1784, and questioned him

extensively on the

settlement of the island in

order to help establish

Britain’s claim to the

island. Here is some of what

he had to say:

“I am arrived so near

the close of life it would

be a serious mortification

to lose Grand Manan and be

compelled by my Countrymen

to move again, or live

under their Government,

merely because we are not

able to prove some act of

Jurisdiction from the

Government of Nova Scotia

has not been exercised

over the Island before the

peace of 1783.

The American claims

being admitted, they will

not only hold Grand Manan

but several other Islands

in this Bay; but

relinquish our claims to

this Island only, and they

will be satisfied, on

account of the fishery

about it; for it is that

they covet more than the

Island” (Buchanan

29-30).

1842

Webster-Ashburton Treaty:

Agreement is

reached on the boundary from

the source of the St. Croix

River to the St. Lawrence

River.

1892 Convention: The

boundary line is laid down

through the islands in

Passamaquoddy Bay…

1908 Treaty:

Since land boundaries were

marked previously with

monuments, mounds or rock

cairns, but water boundaries

had not been shown except by

a curved line through

various rivers and lakes on

its course, and was not

shown at all on the chart of

the St. Croix River, this

treaty provided for such

water boundaries to be

marked by buoys, and other

ways deemed desirable.

1910 Treaty:

The boundary was defined

through Passamaquoddy Bay to

a point in the middle of the

Grand Manan Channel.

1925 Treaty:

Minor adjustments are made

in the boundary line at

Grand Manan Channel.

|

| |

|

References

|

|

Brady, William,

Sailing Master, U.S. Navy. The

Kedge Anchor; or, Young

Sailors’ Assistant, 2nd

edition, R.L. Shaw, 222 Water

Street, New York, 1857.

Butts, Edwards. The

Toronto Star: “Joseph

Barss: The greatest of the

Nova Scotia privateers”.

Web. Accessed July 12, 2013.

Buchanan,

C. (Ed.). The Grand Manan

Historian No. V.

Grand Manan Historical Society,

Grand Manan, NB, 1938.

Canada’s Historic

Places. War of 1812

Timeline: July 1814-December

1814. Web. Accessed May

7, 2013.

Hill,

Judith E. Jewel of the Sea,

1996.

International

Boundary Commission, The

History: The Historic Treaties

of the Boundary Commission.

Web. Accessed July 11, 2013.

Kilby, W.H. (Ed.).

Eastport and Passamaquoddy: A

Collection of Historical &

Biographical Sketches.

Edward E. Shead & Co.,

Eastport, ME, 1888. Web. July

11, 2013.

Smith,

Joshua M. Battle for the

Bay: The Naval War of 1812. Goose

lane Editions & The New

Brunswick Military Heritage

Project. 2011.

Wikipedia. Grand

Manan Island. Web.

Accessed June 27, 2013.

Wikipedia. History

of Maine. Web. Accessed

May 7, 2013.

Wikipedia.

Machias Seal Island.

Web. Accessed May 7, 2013.

Wikipedia. War

of 1812. Web. Accessed

May 7, 2013.

|

Foot Note

1: Although the location of the

proposed fort is given as

“Swallow Tail”, Net Point is

clearly the location of the

intended fort, as the Royal

Naval Engineer drawings show.

|

|

|